The history of agriculture in Nigeria is as old as the Nigerian people themselves, deeply woven into the fabric of their social, cultural, and economic lives. From its early days as a system of subsistence farming rooted in traditional practices, agriculture in Nigeria has undergone significant transformations, shaped by indigenous innovations, colonial exploitation, post-independence policies, global economic shifts, and contemporary technological trends. The evolution of agriculture in Nigeria can be broadly understood through the examination of various historical epochs.

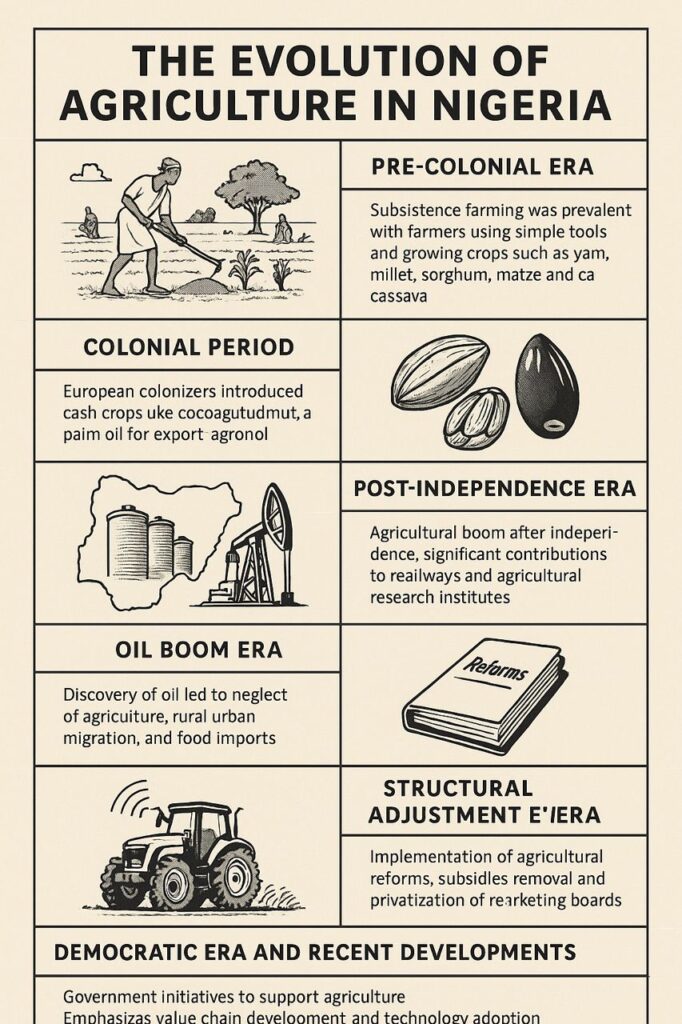

In the pre-colonial era, agriculture in Nigeria was primarily subsistence-based. Farming communities across different ecological zones cultivated crops suited to their environmental conditions. In the savannah and Sahelian north, the dominant crops included millet, sorghum, and later maize, while cattle rearing was also a significant component of the agrarian economy. In contrast, the forest regions of the south favored the cultivation of yam, cocoyam, plantain, and cassava. The Niger Delta and southeastern regions were noted for early oil palm cultivation. These agricultural activities were largely communal, with land being collectively owned and farming methods relying on simple tools such as hoes and cutlasses. Practices like shifting cultivation, bush fallowing, and intercropping were widely adopted, reflecting both an adaptation to environmental realities and the constraints of available technology. Agriculture in this period was not only the primary means of sustenance but also an essential part of cultural expression, with festivals, religious rites, and social structures closely tied to farming cycles.

The onset of British colonial rule at the turn of the 20th century marked a fundamental turning point in the development of agriculture in Nigeria. The colonial administration introduced a new economic orientation that prioritized the production of cash crops for export. Encouraged by British demand for raw materials, Nigerian farmers increasingly cultivated cocoa in the southwest, groundnut in the north, and oil palm in the southeast. These crops became vital to the colonial economy, and by the 1930s, Nigeria had emerged as one of the leading exporters of cocoa and palm oil globally. The colonial government invested in infrastructure such as railways and port facilities to ease the transportation of these commodities from the hinterlands to coastal export terminals. Furthermore, agricultural research stations and institutions were established, including the Moor Plantation in Ibadan and later, the Nigerian Institute for Oil Palm Research (NIFOR). However, despite these developments, the colonial agricultural policy was largely extractive and exploitative, with minimal emphasis on improving food crop production or the welfare of peasant farmers. The neglect of food production eventually laid the foundation for future food insecurity.

Following independence in 1960, agriculture continued to play a dominant role in the Nigerian economy. During the 1960s and early 1970s, the sector contributed more than 60 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and employed about 70 percent of the labor force. Nigeria remained a major exporter of agricultural products, including cocoa, groundnut, palm oil, cotton, and rubber. Regional governments took proactive steps to modernize agriculture through initiatives such as the establishment of farm settlement schemes, agricultural extension services, and commodity marketing boards. These programs were designed to increase productivity, promote rural development, and stabilize producer prices. However, the Nigerian Civil War (1967–1970) disrupted agricultural activities, particularly in the eastern region, leading to food shortages and long-term structural challenges.

The discovery of petroleum in commercial quantities in Oloibiri in 1956 and the subsequent oil boom of the 1970s dramatically altered the trajectory of agriculture in Nigeria. As oil revenues surged, the government shifted its attention away from agriculture, resulting in declining investments in the sector. The newfound wealth from oil exports created a false sense of economic security, and Nigeria gradually became dependent on food imports. Rural-urban migration accelerated, further draining the agricultural labor force, while public policies increasingly neglected the needs of farmers. The consequence was a significant decline in domestic food production and the collapse of Nigeria’s agricultural export dominance.

The economic crisis of the early 1980s, triggered in part by the global collapse of oil prices, forced the Nigerian government to adopt the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP) under the guidance of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank. As part of the SAP, agricultural subsidies were removed, input prices were deregulated, and the commodity marketing boards were dismantled. These reforms were intended to make agriculture more market-driven and efficient. However, the abrupt withdrawal of state support without adequate private sector readiness led to increased hardship for smallholder farmers. In response, successive military and civilian governments launched various programs aimed at revitalizing agriculture. These included Operation Feed the Nation (OFN) under General Olusegun Obasanjo in 1976, which sought to promote self-sufficiency through mass mobilization; the Green Revolution under President Shehu Shagari in 1980, aimed at increasing food production; and the Directorate of Food, Roads, and Rural Infrastructure (DFRRI) in 1986, which attempted to improve rural infrastructure and connectivity.

With the return to democratic rule in 1999, there was renewed interest in agriculture as a tool for economic diversification and poverty reduction. The administration of President Olusegun Obasanjo introduced the National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy (NEEDS), which identified agriculture as a priority sector. This was followed by several initiatives, such as the FADAMA development projects, which received support from the World Bank and focused on small-scale irrigation farming. However, it was under President Goodluck Jonathan (2010–2015) that the most ambitious agricultural reforms were launched. The Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA), led by then Minister of Agriculture Dr. Akinwumi Adesina, aimed to reposition agriculture as a business rather than a development project. The ATA focused on developing agricultural value chains, reducing post-harvest losses, and promoting agro-processing. One of its flagship components was the Growth Enhancement Support (GES) Scheme, which leveraged mobile phone technology to distribute subsidized inputs directly to farmers, bypassing corrupt intermediaries.

The period from 2015 to the present has seen a continuation of agricultural reforms, albeit with new challenges. Under President Muhammadu Buhari, the Central Bank of Nigeria introduced the Anchor Borrowers’ Programme (ABP) in 2015 to provide smallholder farmers with access to credit, seedlings, and fertilizers. The program initially targeted rice and wheat farmers and later expanded to other commodities. While the ABP recorded some successes in boosting rice production, it has also faced criticism regarding loan recovery and implementation inefficiencies. Other notable policies include the Presidential Fertilizer Initiative and increased border control measures aimed at protecting local farmers from smuggled agricultural imports.

Meanwhile, the agricultural sector in Nigeria today faces a host of complex challenges, including climate change, insecurity, land tenure issues, and infrastructural deficits. Rising temperatures, unpredictable rainfall, desertification in the north, and frequent flooding in the south have disrupted traditional farming cycles and reduced productivity. Security threats, such as banditry, farmer-herder conflicts, and insurgency, have displaced thousands of farmers and limited access to farmlands, particularly in the northwestern and northeastern regions. Despite these setbacks, technological innovation is beginning to reshape Nigerian agriculture. Agritech startups and digital platforms are providing farmers with access to market information, weather forecasts, mobile finance, and mechanization services. The growing interest in agribusiness among young entrepreneurs is also a hopeful sign of transformation.

The evolution of agriculture in Nigeria reflects a dynamic interplay of environmental conditions, colonial legacies, policy shifts, and global economic trends. From a subsistence activity rooted in tradition to a sector with commercial and technological potential, Nigerian agriculture has made significant strides, even as it continues to face persistent challenges. The future of the sector will depend on sustained investment, inclusive policies, rural infrastructure development, climate-smart strategies, and the empowerment of farmers as key agents of change. With these measures, agriculture can once again serve as the cornerstone of Nigeria’s economic resilience and national development.

Leave a Reply